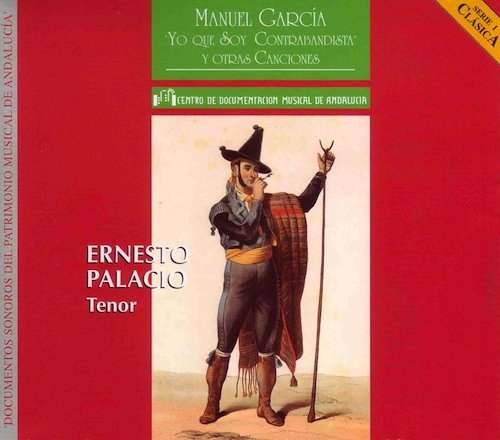

Yo que soy contrabandista

Detail DS - 0114 You can buy this record here 11 € Yo que soy contrabandista Manuel GarcÃa

MANUEL GARCÍA CANCIONES

El Riqui Riqui 2'29” Fortunilla 3’05” Qué tentación de risa 2’01” Parad avecillas 2’50” Caramba 3’03” Tirana 2’40” Bajelito nuevo 1’54” Letrilla española: Las nadadoras 2’33” Cuerpo bueno, alma divina. Polo de "El Criado Fingido” 2’03” San Antón lo bendiga 2'52” Rosal 2’39” Letrilla 1’27” La Rosa 2’38” Tú que no puedes 1’27” La flor del Zurguén 1’35” Abre el ojo, mona 2’46” Llévame a Zurguén 1’46” Serení 1'13" Floris 3'30" Y no lo digo por mal 1'24” Ay ay ay, que sí 2’31” Yo que soy contrabandista. Polo de "El poeta calculista 2'10° Mejor es callar 2'00”

DURACIÓN TOTAL 54'31"

ERNESTO PALACIO, Tenor. JUAN JOSE CHUQUISENGO, Piano. JUAN CARLOS RIVERA, Guitarra.* *Guitarra clásico-romántica (Lourdes Uncilla, 1987, copia de Petit Jean L'Ainé, Paris, ca. 1795).

|

About THE SONGS OF MANUEL GARCIA Manuel del Pópulo Vicente García can only be considered a legend in his own time. A nineteenth century legend in the widest sense of the word. A century and a half ago, the stars of the Italian bel canto (both composers and singers), the German symphonic and Polish and Bohemian piano schools were highly revered and it was in Paris that they consummated their international acclaim. However in the Paris of the 1830's, Spanish music was also revered, and, in general, all that originated in Spain's period of fiery Romanticism. Paris was also where the Seville—born Manuel García found recognition, not only as a singer but also as a composer. His daughter, Michelle Ferdinande Pauline (1821-1910), later to be known as Pauline Viardot—García, was also born in Paris. The goddaughter of Giuseppe Ferdinando Paer, a polyglot from childhood, singer, composer and singing—teacher, as a mezzo—soprano, Pauline Viardot was one of the most versatile figures of the XIX century. She studied with Anton Reicha and Franz Liszt and became a muse for writers such as Ivan Sergeyvich, Turgenev and Alfred de Musset. She was a close friend of Clara Schumann, George Sand and Chopin and inspired Gounod and Berlioz. Brahms and Fauré also dedicated works to her. She came to Spain only once in 1842. Although she was not Spanish by birth she is one of the key figures in the analysis of the propagation of Spanish music across Europe. She is the second protagonist of this recording since she wrote the piano accompaniment for the collection entitled Chansons Espagnoles par Manuel García pére, paroles françaises de M. Louis Pomey, arrangées avec accompagnement de Piano par Mme. Pauline Viardot published by Gérard, Paris 1875, at the time of the centenary of her father's birth and adapted from manuscripts belonging to the García family. The titles and texts were published in French, which obliged Pauline Viardot to make modifications in the adaptation of the French words. Fortunately, the original texts and scores were published on separate sheets in Spanish and these have been used for this recording. In France, where García published the songs included in this edition, he was considered the "premier ténor de toutes les Espagnes", "le Grand García" and generally "un homme pittoresque". As from the end of the Spanish War of Independence, Paris and London (two cities which were important in his career), were key points of dispersal for Spanish music, particularly in song—form. After the War of Independence, Europeans not only adopted the bolero as a dance as well as the fandango and the cachucha, but also Spanish songs gleaned through manuscripts which were occasionally published in Paris and London. These works were extremely popular in aristocratic and bourgeois circles, as evident in the "Boleros de Societé" for piano and voice and piano. Some songs were published in collections of "Aires Nacionales Españoles" for voice, piano and guitar and were almost always the work of such Spanish emigré musicians as Narciso Paz or Salvador Castro de Gistau, or else were printed by such commercially astute publishers as Paccini or Benoist in Paris. The repertoire was to be popularised by musicians like Fernando Sor, Trinidad Huerta, José Melchor Gomis and García himself. Manuel García was to become a pillar of support for exiled musicians who, during the reign of Fernando VII, arrived in France and England by the score. Europe developed an interest in Spain not only through literature but also through music, a fact often ignored in studies concerning Spanish Romanticism which centred mainly on the literary genre. In this sense, the role of Spanish song was highly relevant and shaped the imaginative, picturesque image which European intellectuals acquired with respect to Spain, its inherent forms of expression, its stereotype characters and its philosophies regarding life which would soon become literary clichés. |